Microfluidizer® Technology for

Cell Disruption

This Application Note reviews common cell disruption techniques and explores why Microfluidizer® technology outperforms alternative methods for cell disruption.

Discover practical guidance for achieving optimal cell processing and how the choice of disruption method affects key properties such as particle size, disruption efficiency, viscosity and protein release.

Fast

Fast

Processing

High

High

Yields

Improved

Improved

Filtration

Application

Cell Disruption

Industry

Biopharma

Key Products

BACKGROUND

What are the common methods for cell disruption at lab scale?

French Press: Generates high pressure in a pressure cell. A manually controlled valve releases the pressurized fluid from the pressure cell, resulting in cell rupture. This approach is not scalable or easily repeatable, and it requires significant operator force to open and close the valve. It also presents multiple safety hazards and is difficult and time‑consuming to clean, as cleaning is required after every sample. Although many manufacturers have discontinued the French Press, it is still in use and can be obtained from small suppliers and on the second-hand market.

High Pressure Homogenizers (HPH): These devices are generally considered the next best option to Microfluidizer® processors for cell disruption. However, they present challenges with cooling, cleaning, valve wear, and scalability. When we look beyond simply the percentage of cells ruptured and consider the quality and usability of the resulting cell lysate, the Microfluidizer® processor clearly outperforms HPH systems. As shown in Table 1, the Microfluidizer® processor delivers significantly higher yield compared to an HPH.

Table 1. Even excluding the 20,000psi result for the Microfluidizer, the results are impressively better than the HPH. The 20,000psi results for the Microfluidizer gives 78% more Total Catalase than the best HPH data.| Disruption Equipment Used | Operating Pressure (psig) | Number of Passes | Protein Concentration [Protein] (mg/ml) | Percent Lysis | Specific Catalase Activity (U/mg protein) | Total Product Catalyse (U/mL) |

| HPH | 10000 | 1 | 6.6 | 32% | 160 | 1058 |

| 12000 | 1 | 10.4 | 51% | 108 | 1125 | |

| 15000 | 1 | 13.8 | 67% | 103 | 1425 | |

| 10000 | 3 | 13.4 | 65% | 119 | 1590 | |

| 12000 | 3 | 14.8 | 72% | 85 | 1258 | |

| 15000 | 3 | 14.7 | 72% | 77 | 1127 | |

| Microfluidizer | 10000 | 1 | 10.2 | 49% | 141 | 1444 |

| 12000 | 1 | 12.6 | 61% | 137 | 1729 | |

| 15000 | 1 | 14.7 | 72% | 137 | 2019 | |

| 20000 | 1 | 18.1 | 88% | 118 | 2122 | |

| 10000 | 3 | 17.2 | 84% | 120 | 2066 | |

| 12000 | 3 | 16.1 | 79% | 122 | 1963 | |

| 15000 | 3 | 17.4 | 85% | 107 | 1385 | |

| 20000 | 3 | 20.1 | 98% | 99 | 2007 | |

| Control | 100% Lysis | 20.5 |

Ultrasonication: Utilizes cavitational forces, in which an ultrasonic probe sonicates the cell suspension. This method is typically used for very small sample volumes. Although the equipment cost is relatively low, yield2,4 can be limited due to the high local temperatures generated near the probe, as well as challenges with scalability and noise.

Freeze-thawing: Subjecting the cell suspensions to repeated freeze–thaw cycles exposes them to variable temperatures, which causes the cell walls to rupture. However, this method is not very reproducible, so results can vary significantly, and it is only suitable for very small sample volumes in the milliliter range.

Chemical Lysis: Adding chemicals that soften and rupture the cell walls. Chemicals can be costly and thus scalability is limited. These chemicals contaminate the preparation which may be undesirable.

Mortar and Pestle: Manually grinding the cell suspension. This is labor‑intensive work that can take several minutes, making it neither scalable nor easily repeatable. As a result, it is only practical for small laboratory samples.

Media Milling: For example, using DYNO®-MILLS or similar media milling equipment. While this method is generally effective at rupturing many cell types, there is a risk of contamination from the milling media and challenges with temperature control.

Enzyme pre-treatment: It is common practice to pre-treat cell suspensions with enzymes that soften the cell walls before mechanical disruption. This approach can still be beneficial when using a Microfluidizer® processor, as it may reduce the operating pressure or the number of passes required.2

What are the common methods for cell disruption at production scale?

High Pressure Homogenizers (HPH): the only alternative to a Microfluidizer® processor for larger volumes. Creating higher flow rates typically involves changes to the way the cells are ruptured which causes inconsistency in scaling up. These systems may also require multiple complex homogenizing valves that must be manually disassembled, cleaned, and reassembled by trained specialists—adding significant downtime to production.

APPLICATION

Microfluidizer® Technology for cell disruption

User-friendly and easy to maintain: Customers value that Microfluidizer® processors are straightforward to operate and fast to clean. Multiple users within a laboratory can work confidently with this equipment, as it does not demand specialized skills or extensive training. They also appreciate that the systems require minimal ongoing maintenance.

High Yield: Because the cooling process is highly efficient, the resulting protein and enzyme yields are very good. The contents of biological cells are temperature‑sensitive and often begin to denature at temperatures above 4°C. As reported by Agerkvist & Enfors (Tables 2 & 3), when processing at higher temperatures with an HPH, the Microfluidizer® processor still delivered a higher yield of β‑galactosidase enzyme.1

Exit temperatures of 40–50°C are not necessarily unacceptable, as heat denaturation of proteins depends on exposure time as well as temperature. In the Microfluidizer® processor, residence time is only 25–40 ms2 which is significantly shorter than in an HPH. The HPH heats the sample to higher temperatures for longer periods—resulting in greater denaturation, as reflected in the yield data.

| °C | Microfluidizer | HPH |

| Inlet | 8-10 | 6-8 |

| 1 Pass | 23 | 21 |

| 2 Passes | 27 | 31 |

| 3 Passes | 28 | 40 |

| Dry Weight BioMass g/L | Protein (%) | β Galactosidase (%) | |

| Bead Mill | |||

| 2 min | 49.5 | 62 | 62 |

| 3 min | 49.5 | 72 | 74 |

| 4 min | 49.5 | 79 | 79 |

| HPH | |||

| 1 pass | 48.4 | 66 | 58 |

| 2 passes | 48.4 | 76 | 75 |

| 3 passes | 48.4 | 82 | 78 |

| Microfluidizer | |||

| 1 pass | 101.9 | 62 | 62 |

| 1 pass | 73.2 | 65 | 61 |

| 1 pass | 47.6 | 63 | 61 |

| 2 passes | 47.6 | 79 | 76 |

| 3 passes | 47.6 | 88 | 87 |

| 5 passes | 47.6 | 96 | 97 |

| 10 passes | 47.6 | 100 | 100 |

BENEFITS

Benefits of Microfluidizer® Technology for nab Paclitaxel Drug Delivery

That was quick! The initial comment when we demo our Microfluidizer® processor is “Wow, this is very fast”, because it can process samples in a shorter time than the alternatives. Dobrovetsky reports using 2 passes at 15,000 psi in a M110EH Microfluidizer® Processor vs. 3 passes at 17,000psi in an Avestin EmulsiFlex-C3.4

Lower viscosity: The viscosity of the lysed cell suspension is a critical factor. If viscosity is too high, it makes downstream operations—such as filtration and accurate pipetting—more difficult. After a single pass through an HPH, the cell disintegrate is very viscous and only gradually becomes less so with additional passes. In contrast, cell disruption with a Microfluidizer® processor produces a much lower viscosity already after one pass, which then decreases further with subsequent passes.1,2

Improved Filtration: Cell disruption with the Microfluidizer® processor gives an overall better separation of the cell disintegrates compared to the HPH. A Microfluidizer® processor will break the cells efficiently but gently, resulting in large cell wall fragments. Particles produced by the Microfluidizer® processor are 450nm c.f. 190nm for the HPH. These large fragments are easier to separate from the cell contents, give shorter filtration times and better centrifugation separation than the material produced by HPH.1,2,3,5

IN PRACTICE

Practical Advice for Cell Disruption With a Microfluidizer® Processor

Do not over mix the pre-mix. Using a vortex mixer might entrap air in the cell suspension which, in turn, will choke the Microfluidizer® processor and stop the machine. In fact, it is not actually plugged, but the effect is the same. Gentle agitation is all that is required to keep the cells suspended.

Use ice-water to fill the cooling bath and refresh as needed.

Process cells with a Z-type interaction chamber (IXC). An auxiliary processing model (APM) can be used and placed upstream to provide additional pre-dispersion of cell suspensions.

Match processing pressure to cell type. See tables 4 and 5. Bacterial cells vary markedly in their toughness due to differences between cell wall structures. Gram Negative cells like E. coli are the most commonly used and can be broken fairly easily. Whereas Gram Positive cells are much tougher due to their much thicker peptidoglycan layer presented in the cell membranes, therefore should be treated like yeast or certain tough algae cells with higher shear forces.

Table 4.

Don’t over-process. Take samples after different numbers of passes while running at the recommended process pressure. Although more passes increase the degree of cell rupture, excessive passes introduce too much energy and heat, which can damage protein activity. Over‑processing can also increase viscosity, making downstream filtration and accurate pipetting more difficult.

Ensure complete thawing: Chamber blockages can occur when resuspending cells from frozen pellets if they are not fully thawed, or if the cell concentration is too high. Ensure pellets are completely thawed before processing and, where possible, dilute highly concentrated suspensions with additional buffer.

Avoid heating yeast cells to dryness before adding to a buffer suspension, as this will make a tough cell wall even tougher.

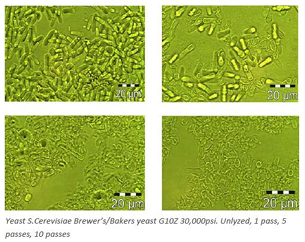

Table 5.

| Cell Type | Pressure | Chamber |

| Mammalian | 13.8-34.5 MPa 2,000-5,000 psi | L30Z (300μm) |

| Bacterial (E. coli) | 82.7-124 MPa 12,000-18,000 psi | H10Z (100μm) or G10Z (87μm) |

| Yeast | 138-207 MPa 20,000-30,000 psi | H10Z (100μm) or G10Z (87μm) |

| Algae | 69-207 MPa 10,000-30,000 psi | H10Z (100μm) or G10Z (87μm) |

References

1. I. Agerkvist and S.O. Enfors, Biotechnol Bioeng., 1990, 36(11): 10831089.

2. J. Geciova, D. Bury and P. Jelen, Int. Dairy Journal, 2002, 12(6): 541553.

3. A. Carlson, M. Signs, L. Liermann, R. Boor and K.J. Jem, Biotechnol Bioeng., 1995, 48(4): 303-315.

4. E. Dobrovetsky, J. Menendez, A.M. Edwards and C.M. Koth, Methods, 2007, 41(4):381-387.

Get your free copy.

Open this application note in a downloadable format.

FURTHER RESOURCES

You may also be interested in these articles:

Brochure: Processors for Nanotechnology Application Challenges

Learn how Microfluidizer® technology produces unrivaled results in uniform nanoemulsions, cell disruption and particle size reduction.

Explore

Explore

Webinar: nab Paclitaxel using Microfluidizer® Technology

Comparison of Biotest HSA and Recombinant HSA for the Preparation of Nano Albumin Bound (nab) Paclitaxel using Microfluidizer® Technology.

Explore

Explore

How it Works: Microfluidizer® Technology

Microfluidizer® Technology delivers superior results by combining a constant pressure pumping system with a unique fixed-geometry Interaction Chamber™.

Explore

Explore